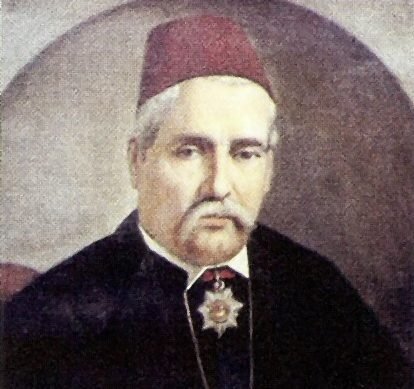

Butrus al-Bustani: The Untold Story of Arab World’s First Encyclopedist

Butrus al-Bustani created the Arab world’s first detailed Arabic dictionaries, an achievement unmatched by any scholar before him. His masterpiece, Muhit al-Muhit, earned him 250 Ottoman liras from Sultan Abdülaziz. The groundbreaking work took fourteen years to complete and revolutionized Arabic lexicography.

The nineteenth-century Arab renaissance (Al-Nahda) saw al-Bustani’s influence grow beyond dictionary creation. He pioneered the first Arabic encyclopedia, Da’irat Al Maaref, and published six detailed volumes about the sciences of his time. His National School, 160 years old now, drew 115 students from Lebanese, Syrian, Egyptian, Turkish, Greek, Iraqi, and Iranian backgrounds, showing his commitment to education.

This piece delves into al-Bustani’s remarkable experience as the godfather of the modern Arabic dictionary while perusing his life, achievements, and lasting effect on Arabic language and education.

Early Life and Education of Butrus al-Bustani

Butrus al-Bustani was born in November 1819 in Dibbiye, a village in Lebanon’s Chouf region. He came from a prominent Maronite Christian family with roots in Baqr Qasha, a northern village between Tripoli and Bsharre. His grandfather’s move to the prosperous town of Dayr al-Qamar in the late eighteenth century led the family to settle in Dibbiye.

Young Butrus showed remarkable intellectual gifts early in his studies. His first teacher, Father Mikhail al-Bustani, noticed his talent and introduced him to Archbishop Abdullah al-Bustani. The Archbishop saw something special in the young boy and made a decision that would transform Arabic scholarship – he sent eleven-year-old Butrus to the prestigious ‘Ayn Warqa school.

Butrus spent ten intensive years at ‘Ayn Warqa from 1830 to 1840. The school’s rich curriculum included:

- Classical languages and literature

- History and geography

- Logic and philosophy

- Literary and theoretical theology

- Fundamentals of legal rights

- Advanced calculus

His time at ‘Ayn Warqa revealed his natural gift for languages. He first mastered Syriac and Latin as part of the core curriculum, but his language skills grew way beyond these foundations. His dedication to learning earned him fame among his fellow students, and people knew him as “the famous student from a famous school”.

Butrus’s language skills became even more impressive during his work on Bible translation. He learned Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek while improving his Syriac and Latin. His gift for languages helped him become fluent in nine different tongues.

The Maronite College in Rome offered Butrus a prestigious scholarship, but he chose to stay in Lebanon. His recently widowed mother’s emotional request influenced this decision, which showed his family’s strong bonds. At twenty, he became a professor at ‘Ayn Warqa, starting his influential career in Arab education and scholarship.

His exceptional command of languages and complete education at ‘Ayn Warqa built the foundation for his future work in translation, lexicography, and educational reform. These early experiences shaped his vision to modernize Arab society through scholarly work, and he became central to Arabic language standardization and cultural renaissance.

Butrus al-Bustani’s rigorous education, remarkable language abilities, and deep knowledge of Eastern and Western scholarly traditions set him apart from his peers. His early years and education not only shaped his intellectual growth but prepared him to become a groundbreaking figure in the Arab cultural renaissance.

Religious Transformation and New Beginnings

“Anyone who studies the histories of religious communities and peoples knows the harm visited upon religion and people when religious and civil matters, despite the vast difference between them, are mixed. This mixing should not be allowed on religious or political grounds. But how often has it had a hand in the present destruction? God knows, and so do you. And since this patriot is not from the band of fools, he also knows.” — Butrus al-Bustani, 19th century Ottoman Arab educator and public intellectual

Butrus al-Bustani’s life took a decisive turn at the time he moved to Beirut in 1840. His departure from Ayn Warqa school stemmed from religious differences. This move led him to American Protestant missionaries and changed his spiritual beliefs and career path forever.

Conversion to Protestantism

Al-Bustani arrived in Beirut with a stellar reputation as a scholar. The American mission noticed his mastery of Arabic, Syriac, Latin, and Italian. His deep study and reflection drew him to Protestantism, and he became one of its devoted followers.

Al-Bustani built a Protestant church in Beirut in 1848, two years before Ottoman rulers gave official recognition to Protestantism. His church’s vision stood apart from typical missionary methods. He wanted to create an Arabic-speaking Protestant church that would appeal to local communities instead of copying Western Protestant practices.

Marriage to Rahil Ata

Al-Bustani’s marriage to Rahil Ata in 1843 shaped his future path. Rahil came from a Greek Orthodox family in Beirut and learned under American missionaries Eli and Sarah Smith. She stood out as one of the first girls to master English at the American Mission School. Her skills let her translate children’s books into Arabic.

Rahil’s widowed mother opposed their marriage because of al-Bustani’s Protestant faith. In spite of that, they married, and their union became a pivotal moment in the Arab renaissance movement. The couple had three children:

- Sarah, born on April 3, 1844

- Salim, who worked with his father on various projects

- Alice, born in 1870

The family lived in Beirut’s Zuqaq al-Blat neighborhood during the 1860s.

Work with American missionaries

Working with American missionaries Eli Smith and Cornelius Van Dyck shaped al-Bustani’s intellectual growth. These connections taught him typesetting, book printing, and public speaking. His first major work came in 1843 when he translated Smith’s Protestant faith doctrine into Arabic.

Van Dyck helped al-Bustani become the first dragoman (interpreter) at Beirut’s American consulate in 1851. He managed to keep this role until 1862, which gave him financial security and time to pursue his educational and publishing work.

American missionaries tried to make al-Bustani an ordained minister in the late 1840s, but he declined. He chose to stay independent while supporting Protestant missionaries’ educational work in the Levant throughout the 1850s.

Eli Smith’s death in 1857 changed al-Bustani’s relationship with the mission. Smith had earlier explained why he didn’t make al-Bustani the evangelical church’s minister in Beirut. He cited al-Bustani’s ‘secular rather than spiritual’ reputation and his love for literature. This prediction proved right as al-Bustani moved toward secular activities while keeping his Protestant educational values.

During these years of change, al-Bustani blended American Christianity with early Arab nationalism. He started in a missionary system that saw the ‘Arab race’ as backward but ended up championing Arab culture and language. This earned him recognition as a father of the Arab renaissance.

The Bible Translation Project

Butrus al-Bustani’s scholarly life changed when he took on the challenge of translating the Bible into Arabic. The American Protestant Mission commissioned this ambitious project to create a standardized Arabic version that would be available throughout the Arabic-speaking world.

Collaboration with Eli Smith

Eli Smith, an American Protestant missionary and Yale graduate, led the translation project. Al-Bustani teamed up with Nasif Al-Yaziji to form a skilled group committed to creating an accurate and refined translation. This collaboration helped al-Bustani build his language skills. He became skilled at Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, while perfecting his Syriac and Latin.

Between 1841 and 1857, Smith and al-Bustani developed a strong intellectual connection. They shared a vision of creating a Bible translation that would appeal to Arabic readers. Their partnership grew beyond translation when Smith taught al-Bustani the techniques of typesetting and book printing.

Translation methodology

Al-Bustani and his team’s translation approach differed greatly from earlier Arabic Bible versions. They created a simpler form of classical Arabic that ended up contributing to Modern Standard Arabic’s development. This method aimed to:

- Make the text available across Arabic-speaking regions

- Control production costs

- Create a writing style that aided wider circulation

The team brought new elements to the translation process. They presented the Bible as a continuous text for the first time, breaking away from traditional fragmentary presentations. The team also used a carefully chosen Arabic glossary that balanced classical rules with modern usage.

Impact on Arabic language standardization

The Bible translation project changed Arabic language development significantly. The simplified classical Arabic they used helped create what we now know as Modern Standard Arabic. Readers across the Arabic continent could now understand the text better.

Al-Bustani’s later work proved groundbreaking when he included Biblical references in his secular dictionary, Muhit al-Muhit. This was the first time an Arabic dictionary used the Bible to explain word meanings. The translation project connected religious scholarship with secular Arabic word studies.

Al-Bustani’s direct involvement in the project remained incomplete. He left the translation work after Eli Smith died in 1857. Cornelius Van Dyck took over and finished the translation with help from Muslim sheik Yusuf al-Asir as copy-editor.

The Bible translation project shaped al-Bustani’s future work significantly. His translation experience influenced his later work in newspapers, word collections, and literary translations. The project made translation his main tool for creating knowledge and laid the groundwork for his broader goal of modernizing Arab society.

Responding to Sectarian Crisis

“As long as our people do not distinguish between religion, which is necessarily an intimate matter between the believer and his Creator, and civic affairs, which govern and shape social and political relations between the human being and their fellow countrymen or between them and their government, as long as our people do not draw a sharp line to separate these two distinct concepts, they will fail to live up to what they preach or practice.” — Butrus al-Bustani, 19th century Ottoman Arab educator and public intellectual

Lebanon faced a turning point in 1860 when violence broke out between religious communities. The Mount Lebanon region saw fierce clashes between Druze and Maronite communities. Muslims and Christians fought violently in Damascus’s Bab Tuma neighborhood.

The 1860 civil war in Lebanon

This conflict ran deeper than religious differences. Trade with foreign nations integrated Ottoman Syria into the world economy and created tensions between communities. The Ottoman reforms of 1856, known as Tanzimat, changed the traditional power balance. These reforms gave equal representation to all religious groups. Lower-class Maronites then competed directly with the Druze elite.

This power struggle led to widespread violence. Thousands of Maronites died in Druze attacks. Villages burned and holy places were destroyed. European powers saw their chance to intervene, claiming they would protect Levantine Christians.

Publishing Nafir Suriyya (The Clarion of Syria)

The bloodshed moved Butrus al-Bustani to write eleven groundbreaking pamphlets between September 1860 and April 1861. He titled these publications Nafir Suriyya (The Clarion of Syria). His message called Syrians to reject religious division and unite as one community.

“Nafir” means clarion or trumpet. This word served as a metaphor to alert readers about the urgent need for national unity. Of course, the word meant more – it referred to mobilizing against a common enemy: sectarianism itself.

Advocating for national unity

Al-Bustani built his vision of national unity around al-watan (homeland). Throughout Nafir Suriyya, he showed Syria as a home for all citizens, whatever their religious beliefs. His words struck a chord with readers: “Countrymen, You drink the same water, you breathe the same air. The language you speak is the same, likewise the ground you tread, your welfare, and your customs”.

He took a balanced approach to the crisis. Unlike his peers, al-Bustani avoided details about the clashes. He didn’t blame specific communities. His main goal was to wake up Syrians from all religious groups and make them think about their shared identity.

Al-Bustani brought the term al-harb ahliya (civil war) into Arabic discourse. He called it “the worst thing under the firmament”. He believed civil conflict’s biggest damage was how it destroyed harmony between Syrians.

His answer lay in keeping religion and politics separate. “There is harm visited upon religion and people when religious and civil matters, despite their big difference, are mixed,” he wrote. He wanted clear lines between religious beliefs and civic affairs. This separation would help create lasting peace and progress.

George Antonious later called Nafir Suriyya the “first germ of the national idea” in Syria. These writings made al-Bustani a leading voice for secular nationalism in the Arab world. His ideas became the foundation for future talks about national identity and religious coexistence.

Educational and Publishing Ventures

Butrus al-Bustani opened Al Madrasa Al-Wataniyya (The National School) in Beirut’s Zokak al-Blat neighborhood during 1863. Religious tensions were high at the time. The school became the Ottoman Empire’s first educational institution that welcomed students from all religious backgrounds.

Founding the National School in Beirut

The National School brought al-Bustani’s dream of secular education to life. Students could enroll whatever their religious beliefs, social standing, or hometown. The school’s complete curriculum featured:

- Languages: Arabic, English, Greek, and French

- Core subjects: Literature, poetry, mathematics, translation

- Advanced studies: History and geography

Rahil Ata, al-Bustani’s wife, played a key role in running the school. Notable educators joined the faculty. Yusuf al-Asir, an Al-Azhar graduate, and the renowned scholar Nasif al-Yaziji were among them.

The school’s student body showed its success. Learners came from Lebanese, Syrian, Egyptian, Turkish, Greek, Iraqi, and Iranian backgrounds. By 1870, 115 students had enrolled. Religious schools and foreign missionary institutions provided tough competition, and the school closed its doors in 1871.

Launching Al-Jinan magazine

Al-Bustani launched Al-Jinan (The Gardens) in January 1870. This trailblazing Arabic-language political and literary magazine came out every two weeks. Each cover displayed the patriotic motto “Love of the homeland is the acorn of believing”.

Al-Bustani’s son Salim took over as editor in 1871. The magazine soared to success. Nearly 1500 subscribers signed up within three years. Readers could find the publication in major cities:

- Middle East: Baghdad, Basra, Cairo, Alexandria, Aleppo, Assiut

- North Africa: Casablanca, Tangier

- Europe: London, Paris, Berlin

The magazine included Arabic history, literature, and European news summaries. It bridged Eastern and Western intellectual traditions beautifully. Sultan Abdülhamid’s tightening grip on free expression forced the publication to close in 1886.

Other publications and their significance

Al-Bustani created many literary and scientific societies that shaped Arab intellectual thought. These included the Society for Education (1846-47), the Syrian Society for Arts and Sciences (1847-52), and the Syrian Scientific Society (1857-60 and 1867-69).

His scholarly works broke new ground:

- “Kashf al-Ḥijāb fī ʿIlm al-Ḥisāb” (Showing the Science of Arithmetic), printed in Beirut in 1848

- “Speech on Arab Culture” (1859) highlighted how knowledge and sciences drive society forward

- “A Lecture on the Education of Women” (1849) championed women’s role in advancing society

Al-Bustani distributed his publications in innovative ways. Al-Jinan used a subscription model that reached readers of all faiths, including Christians, Muslims, and Ottoman sultans. His work consistently promoted separating state from religion and replacing religious bonds with national unity.

Creating Muhit al-Muhit: Revolutionizing Arabic Lexicography

Butrus al-Bustani completed Muhit al-Muhit in 1869 after eleven years of careful work that started in 1858. This groundbreaking Arabic dictionary became a vital step to transition from classical to modern Arabic lexicography.

Innovative dictionary methodology

Al-Bustani’s dictionary compilation method broke away from traditional Arabic lexicography. He wanted to make the language available to teachers and students. His work brought several innovative features:

- Abandonment of traditional phonetic and anagrammatical methods

- Adoption of straightforward alphabetical ordering

- Integration of modern scientific and artistic terminology

- Introduction of brief, practical examples of word usage

Al-Bustani expanded word meanings through historical, psychological, sociological, scientific, and religious explanations remarkably. Muhit al-Muhit stood apart from other dictionaries because it connected classical Arabic heritage with modern usage.

Challenges in compilation

Creating Muhit al-Muhit came with many obstacles. Al-Bustani became the first in Arabic lexicography to balance classical references with modern needs. He wanted to transform classical Arabic into a “living” language that adapted to modern requirements. This made him think over each entry carefully.

The dictionary required extensive research in many areas:

- Scientific terminology integration

- Arts and philosophical concepts

- Modern neologisms

- Traditional Arabic vocabulary

Al-Bustani’s steadfast dedication to maintain scholarly rigor and accessibility created a work of 993 pages. He printed entries and derivatives in red to help readers find them easily. This showed his commitment to user-focused design.

Reception and criticism

Muhit al-Muhit got much attention from linguists when released. They saw it as a reliable reference because of its available approach. The dictionary’s innovative features earned widespread recognition. We used a simplified arrangement and added modern terminology.

Critics mainly focused on two aspects. Some traditionalists questioned reducing classical Arabic features like Quranic and poetic verse citations. Others debated including too much modern terminology. This ended up being forward-thinking as Arabic kept evolving.

The dictionary’s lasting influence showed through its role in standardizing modern Arabic usage. Its method shaped later lexicographical works. It created a framework that balanced classical heritage with modern needs. Without doubt, Muhit al-Muhit became a vital stepping stone toward al-Bustani’s greatest work – the encyclopedia Da’irat al-ma’arif. This encyclopedia expanded his lexical vision further.

The work meant more than just defining words. Through Muhit al-Muhit, al-Bustani advanced his vision of Syrian nationalist ideology. He used language to unite the peoples of the Levant. This approach matched his larger mission to promote cultural unity through standardizing language.

Conclusion

Butrus al-Bustani was a remarkable scholar who reshaped modern Arabic studies through his achievements in lexicography, education, and cultural reform. His masterpiece Muhit al-Muhit changed Arabic dictionary compilation forever. His National School showed that secular education could exceed religious boundaries.

Al-Bustani’s religious conversion changed his life’s path, but his greatest achievement was his vision of unity in diversity. He wrote Nafir Suriyya as a powerful answer to sectarian conflict and advocated for a national identity that went beyond religious differences. His work on Bible translation and later publications set new benchmarks for modernizing the Arabic language.

Al-Bustani’s contributions ranged from innovative lexicography to secular education. This showed his steadfast dedication to Arab cultural renaissance. His impact still guides today’s discussions about language standards, national identity, and religious coexistence in the Arab world. Al-Bustani’s life work proves that scholarly dedication can bridge cultural gaps and promote lasting social progress.