The Woman Who Made Duku a Modern Fashion Statement

Nana Konadu made history as West Africa’s first female presidential nominee at age 67 in Ghana’s elections. Her signature Duku head wrap became more than just a fashion choice – it evolved into a powerful symbol that aligned perfectly with her support for women’s rights in Ghana’s mineral-rich economy.

These head wraps have deep roots in sub-Saharan African culture, dating back to the 1700s. They served as meaningful symbols that showed a person’s age, marital status, and wealth. During her time as Ghana’s First Lady from 1981 to 2001, Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings proudly wore this traditional headpiece while she traveled worldwide to highlight gender issues in Africa. Her activism and distinctive appearance earned her worldwide recognition as a leading voice for strengthening African women’s rights.

The Duku, which translates to head scarf in English, has its origins in Mfantse – the native language of Ghana’s Central Region inhabitants. These traditional wraps showcase diverse shapes, sizes, patterns, and colors that often carry unique cultural significance. Some scholars view Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings as a femocrat who used women’s rights narratives for political advantage. Yet her complex legacy and iconic head wrap continue to intrigue those who study how fashion, culture, and politics intersect.

The Origins and Evolution of the Duku

An array of head wraps across Africa showcases a rich heritage that goes beyond modern fashion trends. These head coverings have existed for centuries on the continent. People used them as visual communication tools instead of simple accessories. These fabrics held deep cultural significance and represented everything from spiritual beliefs to social status.

Different regions gave unique names to these head coverings, which shows their cultural importance. Nigerian people call it gele, while Ghana and Malawi natives use duku. Zimbabweans know it as dhuku, Botswana residents refer to it as tukwi, and South Africans and Namibians use the term doek. Each region developed its own distinct styling methods and meanings.

Royal families first embraced these head wraps. Egyptian pharaohs, Nigerian queens, and Nubian royalty incorporated intricate head coverings into their ceremonial dress. This practice transformed from a royal tradition into a broader cultural symbol over generations.

Head wraps protected people from intense sunlight, yet their role extended beyond practical benefits. Their primary purpose remained communication – a woman’s marital status, whether she was widowed, or her role as a grandmother became clear through specific styles, colors, and arrangements.

Ghana’s head wrap tradition gained prominence when Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings championed it. The duku became linked with religious practices, as women wore them during worship services on Friday, Saturday, or Sunday based on their religious beliefs.

Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings and the Duku

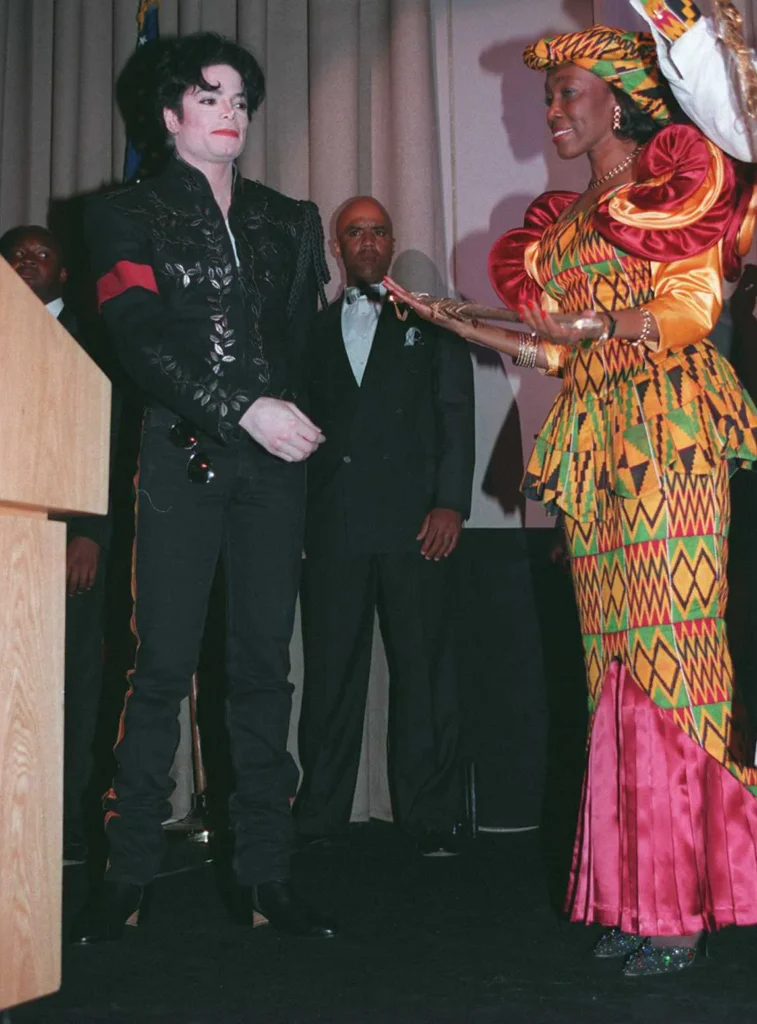

Image Source: Vogue

The duku headwrap became synonymous with Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings’s public image. Her towering headwraps evolved into a powerful national fashion statement throughout the 1980s and 1990s. These weren’t simple accessories. Each duku was an art form that she carefully matched with her outfits and wore with remarkable grace.

Nana Konadu’s unique approach lifted the duku beyond traditional head covering. Her signature style projected authority and self-respect through intricate ties, precise folds, and bold colors. Every arrangement showed considered precision, and her color combinations reflected her spirited personality.

She transformed the traditional headwrap into “a crown of identity, grace, and empowerment” through her consistent presentation. So, Ghanaian women started wearing headwraps not just as practical coverings but as powerful expressions of identity.

Her fashion choices always carried deeper meaning. At the 2019 Fashion Connect Africa event, she explained: “When I started wearing my local fabrics, GTP was almost a collapsed industry and I took a decision to keep wearing just local fabrics”. This dedication ended up inspiring other African first ladies to embrace indigenous textiles.

Nana Konadu’s regal duku helped her “stand above the fray” as she entered the male-dominated political arena. She honored tradition while establishing her unmistakable presence.

Cultural Meanings Behind Duku Styles in Ghana

Duku in Ghanaian culture exceeds mere fashion and serves as a sophisticated language of fabric and form. Each distinctive style communicates specific messages that reflect the nuanced social codes Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings used throughout her public life.

The “Akosombo Special,” named after the Volta River project, creates an elegant silhouette with its dramatic drape at chin level. Market women prefer the practical “Nkuumisee baa don” (meaning “I won’t come back anymore”) because it offers simplicity and functionality.

The “Money swine” or “Keemo mi fee” (“tell me everything”) style appeals to young Ghanaians esthetically. The “Hyia me wo nkwa nta” (“meet me at the crossroad”) once helped romantic partners communicate discreetly.

Older women gravitate toward the “Baakwe ni oya ta” style—a Ga phrase that means “come and watch and go back to gossip”—during funerals and religious gatherings. The aspirational “Odo fa me tu” (“Love, take me in the plane”) and motivational “Onye otsu, onye oye” (“you can spend if you work”) styles carry their own unique messages.

These traditional patterns form the cultural foundation that shaped Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings’s signature look. She drew from Ghana’s rich textile communication tradition while developing her personal style.

The duku head wrap represents much more than decorative attire in Ghana’s rich cultural heritage. Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings turned this traditional garment into a powerful political statement. She created a visual brand that went together with her groundbreaking role as West Africa’s first female presidential nominee. Her signature style—with meticulous crafting, bold colors, and precise folding—showed her authority while paying tribute to ancestral traditions from the 1700s.

This traditional head covering evolved from a practical item to a status symbol, reflecting its deep cultural roots in sub-Saharan Africa. Each region created unique variations that carried specific social messages about marital status, age, and social position. Nana Konadu lifted these traditional meanings during her twenty-year tenure as Ghana’s First Lady. She developed a distinctive style that honored heritage and established her clear presence in male-dominated political spheres.

Without doubt, her fashion choices showed careful consideration beyond mere looks. Her coordinated outfits supported local textile industries and inspired other African women to accept their indigenous fabrics and traditions. The various styles—from the dramatic “Akosombo Special” to the practical “Nkuumisee baa don”—showed how these head wraps work as a sophisticated communication through fabric and form.

Nana Konadu’s signature duku influence reaches way beyond the reach of fashion. While scholars debate aspects of her political approach, her visual identity remains tied to her advocacy for strengthening women in Africa. She turned the traditional head covering into a crown of identity and grace through consistent presentation. This honored Ghanaian cultural heritage while creating opportunities for women in political leadership. Her regal duku reminds us how traditional elements can become powerful symbols of modern identity, cultural pride, and political presence.